Loving the Machine – notes

Peer-reviewed paper: Challenging the Automaton

Background notes and references from my TEDx talk Loving the Machine. These are some of the resources I used c2011 when I was investigating the relationship between Lancashire clog dance, Kraftwerk and early Detroit techno. We can’t say with certainty that industrial music was born in post-war Germany or Detroit. It’s undoubtedly had many beginnings – and one of those was in the cottton mills of Lancashire, in the early nineteenth century, when women clog dancers mimicked the sounds and actions of the factory machines.

Peer-reviewed work

Since compiling these notes, the work in this talk has been discussed in two peer-reviewed publications:

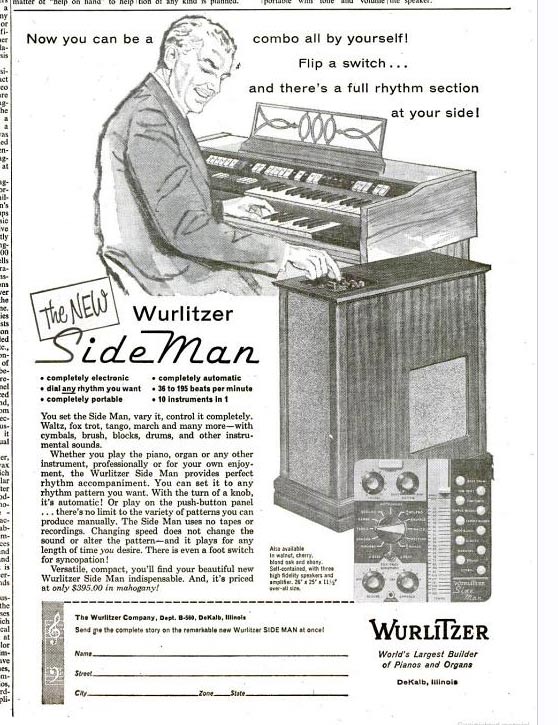

Angliss, S: “Mimics, menaces or new musical horizons? Musicians’ attitudes towards the first commercial drum machines and samplers”.

In Material Culture and Electronic Sound, edited by Frode Weium and Tim Boon (with forward by Brian Eno). Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2013.

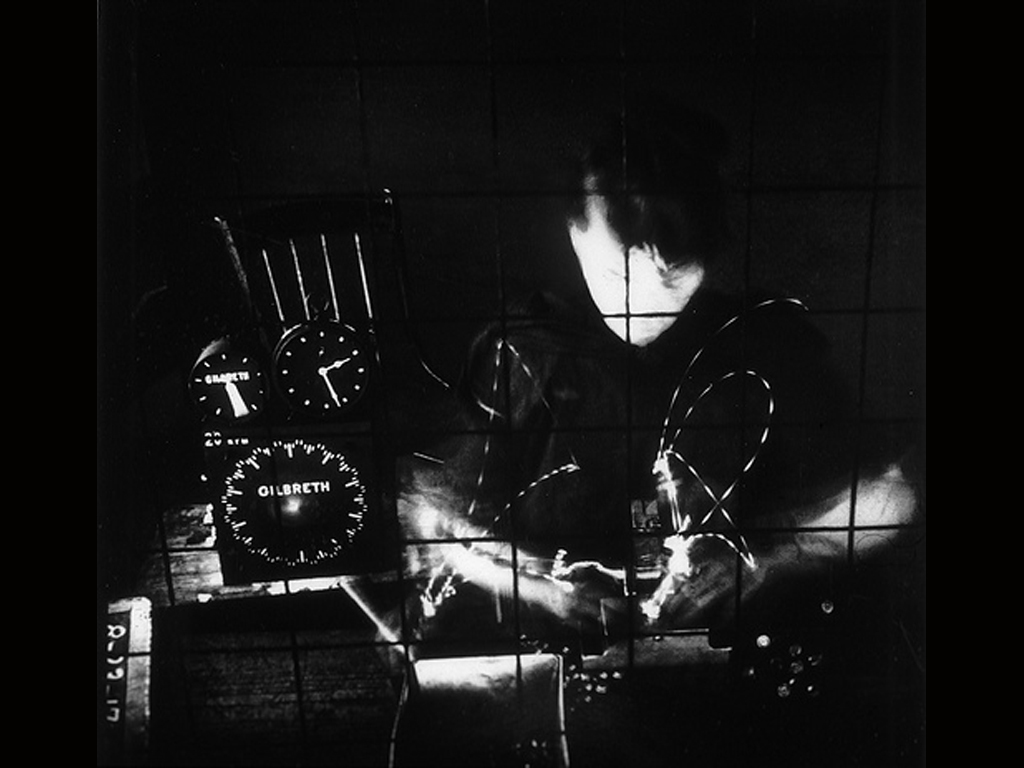

Radcliffe, C and Angliss, S: “Revolution: Challenging the automaton: Repetitive labour and dance in the industrial workspace”.

In Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts Vol 17, Issue 6, 2012.

The Machinery – 1804 industrial dance culture

‘The Machinery’ – a dance piece from 1804 which I reinterpreted with performer and historian Caroline Radcliffe – is one of the topics of this talk. Since 2011, we’ve performed our version of The Machinery many times at music festivals, algorithmic arts festivals, museums and more.

A performance of The Machinery at Algomech Sheffield was filmed by Jon Harrison who then worked with us to create a tourable, large-scale video triptych of the piece. Funded by Arts Council England, this was first exhibited at Ironbridge Gorge Museum, Coalbrookdale. It was due to go on tour in 2020 – sadly the tour was postponed due to the Covid pandemic. A smaller preview of the work was seen in the 2018 automaton exhibition ‘The Marvellous Mechanical Museum‘, Compton Verney.