THE EXPERIMENTAL CONCERTS

By 2003, I was certain I wanted to explore the effects of infrasound – and I realised I needed a team of experts in psychology to design any experiments. So I contacted parapsychologists Richard Wiseman and Ciaran O’Keeffe. I also contacted acoustic consultants from the National Physical Laboratory (Richard Lord and Dan Simons) as I needed to produce pure infrasound at levels high enough to flood a concert hall. I worked with the pianist Genia who would perform live on the night. We brought in a number of other composers and artists to create a programme for an experimental concert. Our aim was explore the tantalising claims about infrasound in a musical setting and put them under scientific scrutiny.

Together, we set up Soundless Music, two counterbalanced experimental concerts in the Purcell Room, London. These took place within 90 minutes of each other on 31 May 2003. The same music was played in both concerts but each concert was laced with infrasound in different pieces. Neither the performers nor the audience were told when the infrasound was present. If it appeared in pieces, 2, 7 and 8 in one concert, for example, it appeared in pieces 3, 5 and 6 in another. The only person to know when the infrasound was present, Ciaran O’Keeffe, was (literally!) locked away in a cupboard for the entirety of both concerts.

At certain points in the concert, the audience were asked to fill out questionaires to report on any feelings they had during previous pieces. They were also asked to report on how excited/bored they were during the pieces.

The counterbalancing was an important element of the parapsychologists’ experimental design. Everyone attending was buying a ticket because they knew we were working with infrasound – and the publicity suggested we were dabbling in the realm of ghosts. So there was likely to considerable priming and suggestion at play – the audience were expecting something unusual to happen. However, no one, apart from Ciaran, knew when the audience were experiencing pieces laced with infrasound and when they were not. Thus, we could expect to see increased reports of strange sensations during the concert. But if those reports were always more prevalent, more marked or more consistent in nature during the pieces laced with infrasound, then we may have evidence of an interesting effect.

Our results were tentative and our statement about the project were based on an analysis of the results by Richard Wiseman and Ciaran O’Keeffe. I need to leave the details of the statement to the parapsychologists but the summary is: when the infrasound is present, people did report more feelings of unease, a sense of presence. And there is tentative evidence that this is the case, even among audience members who weren’t aware of the presence of the infrasound. It was a tantalising but inconclusive result – and I would love to take this research further.

A year after this experiment, I took a masters in biologically-inspired robotics in the COGS department of Sussex University. Among many other things this masters gave me confidence to design my own psychoacoustic experiments. I have many ideas for follow-up research and would love to find funding and a pocket of time to follow them up.

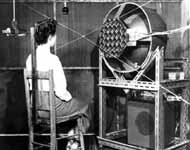

The Pipe – and a critique of the resultant technique

I’ve had many enquiries about the infrasonic pipe we created for this experiment and have written up a few details on separate page.

On this page, I’ve also included a critique of the resultant technique for infrasound generation. It’s a time-honoured way to create infrasound but I find it hugely problematic for anyone investigating the psychological effects of infrasound. A number of subsequent research experiments into infrasound’s reputed effects have, in my opinion, insufficiently addressed this issue.