John Ramlings

October 1st 1794

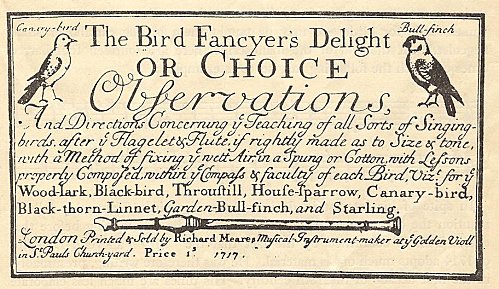

The New and Complete Bird-Fancyer; or Bird-Fancyer’s Recreation and Delight. Containing the Newest and Very Best Instructions for Catching, Taking, Feeding, Rearing, &c. all the Various Sorts of Song-Birds, particularly Nightingales, Larks, Goldfinches, Bullfinches, Robins, Canary-Birds, Black-birds, Thrushes, Starlings, Linnets, &c. &c. Including, among other particulars, A full Account of all their several Distempers, and the best Methods of curing them. Likewise the surest Means of distinguishing the COCK from the HEN, and of learning them to sing to the greatest Perfection. Together with Many other useful Particulars relative to Singing Birds, too numerous to mention in a Title-Page.

The whole Revised, Corrected, and Improved, By Mr. William Thompson, Late Gardener to the Duke of ANCASTER (sic), and Author of New Gardeners Calendar; who has made the Management of Birds his favourite Study upwards of Twenty Years.

Assisted by the most eminent Fanciers.

Embellished with a beautiful Frontispiece, elegantly designed and executed.

London

Printed for Alex. Hogg, at the Original King’s Arms, No. 16, Pater-Noster-Row

[Price only one shilling]

Preface

No well executed work of this kind having yet appeared, treating wholly of Singing-Birds, we here present the Public with one, compiled from our own observations, and confirmed by the experience of others, who have been curious in the breeding and bringing up of Singing-Birds. And

as nothing magnifies and sets forth the power of the Supreme Being more than these pretty harmless animals, whether we reflect on their velocity, beauty, or the variegated colours of their feathers, so, in every respect they raise infinite delight and satisfaction to their keepers, and sweetly recompence their trouble and charge in bringing them up, by their pleasant harmony. We enjoy in our houses or aviaries, all the melody of the woods. …

How to stop a Linnet, or any other Bird, and make them sing after they moulted off

The stopping of a bird is of greatest use to the bird-catchers, and likewise such as would have them a sweet song, you must let your bird, before you stop him, be a year old or better, and keep him in a back cage, so that he may be able to find his victuals in the dark; you may put him in a stop about the middle of May. The nature of a Stop is, to have a case made fit for the purpose, then put in your birds and leave the door open till you are satisfied they have found their meat and water, then darken them by degrees ‘till they are quite dark, and when you see they have found their meat and water then cover them with a blanket or any thick cloth that is warm, keeping them very hot; you may look at them, once in two or three days, give them fresh water, and blow their seeds:

It is not best to clean their cages above once a month, by reason the hotness of their dung forces them to moult. You should take a bit of stick or knife, to keep their dung down, to prevent dirtying their feathers, and then let them continue in this close stop for three months, by which time they will be moulted off, then open them a little and a little by degrees; take off the blanket first, and let them stand so three or four days, then open the door a little way, then take them out and clean their cages, after that put them in again with the door half open for two or three days longer, then take them out and put them in a warm place, so that they come to the air by degrees; put them a little beet-leaf and liquourice in the water, this with a blade of saffron, which is a very good thing, when he is drawn of a stop. After you have drawn them out of a stop, you will find them to sing still more and more, so that they will be for the bird-catcher’s use, or to learn any other birds their song; those birds will continue in song ‘till about Christmas, or after, by which time most young birds are come to their song.

The bird-branchers are very plentiful to be catched in June, July, or August, and likewise flight-birds about Michaelmas in great quantities: I have known forty of fifty dozen catched in one day with clap-nets. …

The Bullfinch

This is a very fine bird both for its beauty and learning songs, but his natural one is very indifferent. He may be learned to pipe almost any tune at command, you may also learn him to talk. Some are tought to speak and whistle at command; and when they have once got a tune, they seldom forget it, not even if they hand amongst other birds. They are very valuable, if well brought up, and are sometimes sold for nine or ten guineas a bird. …

How to feed them

You may feed them and bring them up the same way as you do a Linnet, only when they feed themselves, give them more canary-feed than a Linnet. Generally give them the better half canary-feed, and the rest rape; and if you find them out of order, give them a little fine hemp-feed, and a little saffron in the water; give them likewise a little Woodlark’s victuals, the same as you would do a Linnet. Take them out when about twelve or fourteen days old; when kept four or five days, or a week, you may begin to pipe, whistle, or talk to them what you have a mind they should learn. A gentleman that piped to one from a fortnight old to two months, and then being obliged to leave his bird and go into the country for six months, before he returned his bird whistled nearly three parts of the tune, notwithstanding he had no-body to pipe or tune to him in his absence. …

The Canary-Birds

These birds we formerly had brought from the Canaries, and no where else, and are generally known by that name; but we have abundance of that kind come from Germany, so we call them by the names of the country, German birds, but I believe their first original were brought from the Canary islands. Those brought from the Canaries are not so much in esteem with us as formerly, for those brought from Germany and France far exceed them in handsomeness and song. German birds having many fine jerks and notes of the Nightingale and Tit-lark.

The nature of the Canary-birds is quite contrary to all others, for as other birds and subject to be fat, they never are, (I mean the cocks when in song) for the great metal of the birds, and his lavish singing, will hardly suffer him to keep flesh on his back. …

To chuse a bird for song

If you hear him sing before you buy him, then you are sure you have not bought a hen for a cock. As to the song, I count it good, when it is begun something like the Sky-lark, then running on the notes of the Nightingale, which if he begins well, and holds it long, nothing in my mind can be sweeter; but as the fancies of men are as different as either the colours or songs of the bird, so their eyes and ears are the best judges for their fancies, yet I shall not fail to give me opinion and judgement to those who have not had experience in this delightful and innocent amusement.

The next obervation is, a bird that begins with the sweet of the Nightingale, and ends with the song of the Tit-lark, is both harmonious, sprightly, and very delightful to the ear.

These notes are distinguished by the Sweet Jugg, followed by a swelling slut/flut, with the water-bubble, and then the sprightly song of the Tit-lark, chewing and whisking several times in a breath; a bird that will go on sweetly thought his song in this manner, withouth breaking off, may be said to be a good song bird.

Some fanciers are pleased when a Canary-bird only sings the song of the Tit-lark, which is indeed very pleasant and delightful. Others only fancy that bird which begins like the Sky-lark, and holds his song all the while in the same manner, having long notes and sweet, but I think not much variety in it.

If these instructions may not as first truly qualify a person, let this serve in general, that they chuse which is most agreeable to their own ear, and that which holds the song the longest, without breaking off short, with harsh scraping notes, or disagreeable whining. …

To know a cock from a hen

… The way then to distinguish between the cock’s song, and the hen’s jabbering is, that the cock, let him sing ever so indifferent, almost every time he strikes a note, you may easily perceive the passage of his throat to heave with a pulsive motion, swelling like a little pair of bellows all the time he is warbling out his pretty notes, which never happens to a hen; for let her make what noise she will, and resemble singing ever so well, this motion is never observed in her throat as it is in the cock’s.